An American In Jerez

Image Posted on Updated on

When Alex Russan was a young college student he had his first taste of sherry. In an instant, he was hooked. “It was the most complex thing I had ever tasted. The unique flavors really moved me.” In the following years, the California native worked as a coffee buyer and simply indulged his passion for sherry the way most of us do, by simply drinking a lot of it. As the sherry renaissance began to flourish, however, his entrepreneurial instincts kicked in, and he saw an opportunity to turn his passion for sherry into a business. The result is Alexander Jules, a line of limited production, barrel-selected sherries, which made their debut last fall.

Sherry business is an old business, dominated by big shippers who can often trace their lineage back to the early 18th century. Many of them have been British—Harveys Bristol Cream, Byass of González-Byass, Sandeman—but Russan is the first American to bottle Jerez sherries. One of the factors that makes this possible is the fragmented structure of the industry. Rarely do the producers, who age and bottle the wine, own their own vineyards. Most buy their base wine from growers or an already aged wine from an almacenista. Traditionally, the goal for many of the sherry houses has been to maintain consistency, which is accomplished through blending the different barrels in their soleras, which are themselves blends of vintages. Beginning in the 1980s, however, Lustau recognized a market for smaller, more artisanal sherries and began bottling wines from individual almacenistas and featuring their names on the label. More recently, Equipo Navazos entered the market with their La Bota series, sherries from selected barrels that they thought expressed unique character but weren’t being bottled and sold. Bodegas can have hundreds of barrels (González Byass is the largest with 80,000), but inevitably not all are commercialized. This is where Equipo Navazos, and now Alexander Jules, have stepped in.

Having honed his palate over the years with specialty coffee (there are many similarities with wine) and recognizing that the interest in sherry was only growing stronger, Russan took the leap and, in August of 2012, began contacting the Jezez bodegas. The owners were all open to his proposal. “I was pleased with how receptive people were.” During his first trip to the region he tasted through barrels at 15 bodegas. “Once I have a sense of the spectrum of variation in the solera, I have an idea of what I’d like to focus on or accentuate in that solera. I’ll search for the barrels I feel represent that and will work well together. I look for complexity, cleanliness, precision of flavor, depth and elegance.” A few thousand emails and calls later, he bottled his first wines in May 2013.

In the last few years sherries have been increasingly bottled en rama, which means with minimal or no clarification or filtering before being bottled. This keeps the wine’s inherent characteristics as intact as possible and adds to the complexity and body. It’s as close to tasting a sherry in barrel as possible. Although Russan’s sherries are not labeled as such they are minimally treated. “Before en rama bottlings were common, most Finos and Manzanillas seemed fairly lean, austere wines, however, tasting them from the barrel they are often weighty, lush wines.” These in-barrel qualities are what he seeks to preserve in bottle.

Having tracked down a bottle of the 6/26 Amontillado at Slope Cellars, a wine store in Brooklyn, I can say that the sherry delivers in spades. This particular wine comes from a 26 barrel solera from Bodega Argüeso in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, a city on the Atlantic coast and the home turf of Manzanillas. The wine spent five years under flor followed by another five years aging oxidatively. Out of those 26 barrels Russan selected wine from 6 of them to be bottled, hence the 6/26. Per Russan’s instructions I sampled it over the course of four days. Initially this golden wine smelled of roasted almonds and camomille, a distinctive quality found in Manzanilla sherries. On the palate it was bone dry and crisp but with a soft, creaminess to the body. Flavors of mushrooms, raisins, baguettes, and brine went on a surprisingly long time. A day later the smell of butterscotch rose to the fore before receding the next day. By day 4 the butterscotch had been overtaken by scents of mapled walnuts and raisins. On the palate it remained crisply dry and creamy and tasted of camomille, almonds and olives. I did as the Spanish do and paired it with Iberico ham, Marcona almonds, and Manchego cheese.

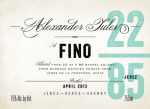

In addition to the Alexander Jules 6/26 Amontillado, 500 ml, $40, Russan currently has two other sherries on offer: Alexander Jules Manzanilla 17/71, which comes from a nearly 200-year-old solera at the same bodega as the Amontillado and is bottled en rama, and Alexander Jules Fino 22 /85 from the Fino Celestino solera at Sanchez Romate in Jerez de la Frontera. These wines are aged an average of eight years and also bottled en rama.

His future plans include another release of the Manzanilla and Amontillado as well as a new Fino, but the real highlight, he says is an “old Oloroso from barrels that were untouched for about 40 years, after having been essentially lost.” These barrels were initially filled with about 500 liters (of already old wine). After 40 years there’s been significant ullage, leaving about about 200 liters. “A really intriguing, concentrated wine and a unique story.”

A Heavenly Wine from Ancient Vines

To enter Deborah Hall’s world requires traveling from a four-lane highway to a two-lane road, followed by a barely noticeable, rutted dirt track to an unmarked gate, and finally through a lavender-scented threshold into a cathedral-ceilinged converted barn. Hall’s Gypsy Canyon vineyard, 50 miles northwest of Santa Barbara, is so tucked away and so off the grid you feel like you’ve stepped back in time. But this is precisely why I’m here—to taste her Gypsy Canyon Angelica, a fortified wine made with grapes from century-old vines using a recipe followed by Spanish missionaries in the 1700s.

On the wooden coffee table in her living room Hall sets out a plate of cheese and two glasses while a small dog pads around sniffing for treats and three others press their noses against the glass door. Hall is as warm as she is gracious and is equal parts earthy and ethereal. It’s an apt description too for The Collector’s Pinot Noir, which she pours as a prelude to the Angelica. It’s a wine worthy of attention in its own right—finely chiseled and nicely concentrated, a world apart from the big, bold, fruity school of New World Pinots and one of the best I’ve had in three days of tastings. But it’s also a critical part to Hall’s story, which she begins to describe as we swirl, sniff and sip.

Pinot Noir is what lured Hall and her late husband from a comfortable life in Los Angeles to one closer to nature. When they bought the property in 1994 the arable land had been planted with lima beans, while cattle grazed in the surrounding hillsides. As they set about replanting with Pinot Noir they discovered an east-facing, sandy hillside of gnarly old vines overgrown with sagebrush. “They were barely recognizable as grape vines and produced lots of these tiny little berries,” Hall tells me. At first the grapes were thought to be Zinfandel and for a few years she sold them to a local winery. A test at UC Davis in 2001, however, determined that they were actually Mission grapes, and, just like that, no one wanted them. Mission grapes (aka Pais in Chile and Criolla in Spain and Argentina) had been brought to the Americas in the 1500s by Spanish priests and used to make sacramental wine and brandy. At one time it was the most widely planted grape in California but has now dwindled around 1000 acres. One winemaker suggested she rip them out, but she loved these old vines and set out to discover their history.

Hall brings out a small dark bottle, and immediately you can tell this is something all together unique. The 375 ml bottles are hand blown and contain the winery’s seal. “That’s how they made their bottles back then, and I wanted to carry on that tradition.” The labels too have a historical craftsman-like quality. The paper is handmade, printed with a 19th century manual letterpress and embossed with a depiction of the mission vine that had been painted on a mission wall by the Chumash Indians. As a final personal touch, the cork is sealed with wax from the vineyard’s beehives.

As she pours the Angelica she pulls out a copy of the book that turned out to be her Holy Grail for Mission grape winemaking. She had discovered the old tome in the Santa Barbara mission, which held the archives of all 21 Spanish missions after they were secularized in 1833. The Franciscan priests, who had been sent from Spain to convert the native population to Catholicism, brought with them orange, apple, pear and fig seeds, as well as manuals for cultivating crops, animal husbandry, and most importantly for Hall, winemaking. There, among the stacks of old books written in Old Spanish she found the Agricultura General, a detailed guide for growing grapes and making wine published in 1777. “I liked the idea of the priests reading this by candle light,” she says.

The book contained four recipes, but in reading through old correspondence Hall determined which technique produced the most favored result. Mission grapes make a fairly neutral, uninteresting dry wine and would easily spoil during transport between missions in the hot California sun. But when fortified, the wines become nuanced and delicious as well as more stable. Although Mission grapes had long gone out of fashion, Hall figured if the padres could make a delicious wine out of them so could she.

Hall lets the grapes ripen as late as possible, harvesting around 28 brix, which is usually in late October or early November. The grapes are then immediately pressed without any extended maceration as would be done with port grapes. Fermentation takes place in half-filled old French oak barrels, which no longer impart any oak flavor. When alcohol reaches 12% she adds neutral grape spirit to halt fermentation. This brings the total abv to 18% with 9% residual sugar. The wine then stays in barrel, on its lees (spent yeast), for another four years and is never topped up. The lees lend the wine an additional level of complexity and mouthfeel, while the exposure to oxygen brings about dried fruit and nutty flavors. At bottling time she takes a bit of wine from each aged barrel to create a final non-vintage blend. The result is a wine with a rosy, amber tint and a lighter body than you might be used to with dessert wines. It has a refreshing amount of acidity that perfectly balances out the sweetness, and tastes of raspberries, cherry jam and dried figs, sprinkled with a hint cinnamon. Hall likes to pair it with five-year-old Gouda, whose salty, crystalline nuggets provide a perfect foil for the wine’s sweetness.

Sated with wine and cheese, we leave the dogs behind and head out into the three acres of Mission vines, which she named the Doña Marcelina vineyard after the area’s first female winemaker. “I love to be out here in the spring when the grapes are flowering. They smell just like the wine.” The sun is blisteringly hot. The fog that flows in every night from the nearby Pacific and cools the grapes (the reason the region has become a hotbed for Pinot Noir) burned off hours ago. Through local records Hall has managed to date the vines to 1887. Although the twisted, elephantine trunks, some a foot thick, look every bit their 127 years, the loose cluster of grapes shine a bright healthy green. In a few months they’ll ripen into deep violet before being transformed into a sweet, beguiling drop of history.

Gypsy Canyon wines can be found on her website: http://gypsycanyon.com

Trois Pinot Noir, 2012, 750ml, $95

The Collector’s Pinot Noir, 2012, Sta Rita Hills, 750ml, $110

Ancient Vine Angelica, NV 350 ml, $150

Best New Wine Blog Finalist!

I’m thrilled and honored to be selected as a finalist for Best New Wine Blog 2014. Be sure to cast your vote before June 19th at 11:59pm PDT. Congratulations to all the finalists!

Best New Wine Blog:

Finalists:

Alsatian Pinot Gris–the Unpinot Grigio

From the first drops out of the bottle you can tell this is not your typical Pinot Grigio. As the golden liquid fills the glass and you catch scents of apricot and honey you might have a moment of dislocation. That’s because it’s Pinot Gris from Alsace. Same grape, completely different wine.

Although the Italian version may steal all the limelight (and market share), the very same grape grown just over the Alps produces a completely differently style of wine. Where the Italian version is light, crisp and always dry, the Alsatian one is rich, full bodied, and made in a range of styles from dry to sweet. Where Pinot Grigio delivers lemon and almond (though not much else), Pinot Gris offers up a complex plate of apricots, orange, honey, and honeysuckle. The two styles are so distinct that in New World regions where the grape is grown, such as Oregon and California, the wine is labeled according to style: Pinot Grigio for light and crisp, Pinot Gris for full bodied and fruity.

One of the benchmark producers in Alsace is Olivier Humbrecht, who Robert Parker once declared “may well be the best winemaker in the world.” That is high praise, especially since all the vineyards of Domaine Zind-Humbrecht are farmed biodynamically, a practice Parker has a mixed record on, to put it mildly. But Humbrecht is a serious winemaker, with a pedigree of 16 generations behind him and a Master of Wine degree. Since 1997 he’s been tending his 40 ha of vineyards (4 grand crus and 6 single vineyards) according to the biodynamic principles set forth by Rudolph Steiner in 1924. He is also currently president of Biodyvin (www.biodyvin.com). The key concept is in thinking of the vineyard as a whole. Maintaining the health of the soil is key to maintaining the health of the vines. To that end he uses no chemical pesticides or herbicides. For Humbrecht, who was recently in New York, it was a revelation. “We solved so many problems that we struggled to deal with in conventional farming.”

It is often said that 90% of winemaking occurs in the vineyard. Whereas most Italian Pinot Grigio is grown on the fertile valley floors, which leads to vigorous growth, high yields and hence less concentrated grapes, in Alsace vineyards are planted on south-facing hillsides and yields are kept low, no more than 40 hl/ha. In Italy the grapes are harvested early resulting in high acid, simple citrus flavors of a mass-market Pinot Grigio. In Alsace, the distinctive feature is that the region sits in the rain shadow of the Vosges mountains, resulting in dry, sunny autumns. Without the ominous threat of rain the grapes enjoy a long ripening season. When Mother Nature cooperates late harvest (Vendage Tardive) and botrytised dessert wines are possible. As Humbrecht told me, “it entirely depends on the late climate (alternance of cold nights and sunny days) and the initial acidity balance (low acid vintages do not make the best sweet wines). It all comes to finding out how the vineyard expresses itself the best.”

In the winery Humbrecht maintains a minimalist approach. “Once the grapes are harvested, I personally do not decide whether the wine should be dry or sweet. Wild yeast will decide for me, and their decision is mostly based on the balance of the wine. The higher the acidity, the more chance there is to see the fermentation stopping before the end, and vice versa.” He allows his fermentations to proceed slowly and lets his wines spend at least six months on the gross lees. He bottles the wines 1 to 2 years after harvest and filters only once at the end of winter while the yeasts are still dormant and only when all the yeast has settled at the bottom of the cask.

One of the conundrum’s for wine buyers when facing all those tall slim bottles in the Alsace section of a wine store is how to know whether a wine is dry, off dry, or dessert-level sweet. It’s a problem even for the winemaker’s family members themselves. In 2002 Humbrecht’s wife found a bottle of Riesling Turckheim 1990 in the cellar, but since they hadn’t tasted it in a while she couldn’t remember the level of sweetness. “I thought to myself that if she doesn’t remember, how could our customers, who probably had less chance to taste the wine than us?” Humbrecht devised a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the driest and 5 the sweetest that has appeared on all his labels since the 2001 vintage.

This Pinot Gris qualifies as a level 2 on the sweetness scale, which means that while there is a hint of residual sugar, it mostly gives the wine a rounder mouthfeel. The perception is of a dry wine, albeit rich and full of apricot, lemon zest, honey, orange blossom and a distinctive minerality. It comes from a parcel of old vines, planted 60 or 70 years ago producing a wine of marked concentration. And finally, what to pair with it?

The Many Moods of Chenin Blanc

It makes no sense that Chenin Blanc, a temperamental, difficult-to-ripen grape, should thrive in the cool, northern folds of France’s Loire River Valley, a region meteorologically challenged for growing any type of vines. Chenin likes to flower early in the spring, exposing its tender buds to not-uncommon frosts, and takes its own sweet time ripening in the fall, complicating harvests by not doing so at the same time. But thrive here it does, and it has for centuries, according to ampelographers who can trace its origins to the 9th century.

Chenin owes its livelihood to a tongue-tingling level of acidity, which in turn gives the grape a surprising amount of versatility, not unlike Riesling. Depending on where it’s grown (both climate and soil are factors) and the weather conditions at harvest, winemakers can make any style of wine they deem best, from bone dry to luscious dessert wines and everything in between. In Savennières (part of Anjou) the style is dry with waxy, floral notes, but just across the river the specialty is botrytized dessert wines from Coteaux du Layon, Quarts du Chaume and Bonnezeaux. Upstream in the region of Vouvray the predominant style is demi-sec, although dry and dessert wines are made as well.

One producer who does it all is Domaine Huet, the preeminent star of the Loire, whose wine has become the standard bearer for Chenin-based wines. In 1928, when Victor Huet bought his home and attached vineyard Le Haut Lieu just outside of the town of Vouvray, he did so with the hope that a quiet life in the country would ease the debilitating effects of the mustard gas poisoning he’d suffered in WWI. His son Gaston Huet, however, himself a WWII hero, put his heart and soul into the winery and set the bar for producing exceptional wines. He eventually bought two more vineyards (Le Mont and Clos de Bourg) and in the late 80s began farming biodynamically. Gaston and his wife had three children, but the only one to show any interest in the winery was his son-in-law Noël Pinguet, who took the helm in 1976. By then Gaston’s duties as mayor of Vouvray, which he’d been since 1947, were demanding more of his attention.

During the subsequent decades, Pinguet and Huet’s wines became the benchmark for the Loire, topping out best-of lists year after year. Then, in 2002 Gaston Huet died, and the winery was sold to Anthony Hwang, a Filipino-American businessman who also owns the Tokaji estate Királyudva in Hungary. Pinguet was supposed to stay on to make the wine until 2015 but, as with so many other buyouts where the winemaker remains, there was a falling out. Hwang had recently put his daughter, Sarah, in charge and press reports indicate that she (and presumably with her father’s blessing) wanted to focus more on the dry styles. Producing the sweeter styles of wine is a far more hazardous endeavor since the grapes need to stay on the vine longer, ideally until they’ve shriveled to raisins or succumbed to botrytis, in the case of the moelleux. But these were the wines that made Huet famous, and in October of 2011 Pinguet abruptly resigned.

It’s too soon to tell the exact impact Pinquet’s absence will have on wine quality or the styles produces. Huet did make demi-secs in 2012 and 2013, but no moelleux. Hail damaged a good portion of the crop in both years so that might be all the explanation there is. Even Pinguet only made moelleux in years when the conditions were right. Remaining at the winery are Benjamin Joliveau, who had been under Pinguet’s tutelage before he left, and Jean-Bernard Berthomé, the chef de cave, who will be in charge of both the winemaking and the vineyards. Berthomé has been at Huet for 35 years, and one would expect that some of Pinguet’s and the late Gaston Huet’s methods and philosophy were deeply instilled in him. For now there’s no reason to suspect that they won’t continue the high standards that earned Domaine Huet its esteemed reputation in the first place. But let’s hope that they and the Hwangs have the fortitude to continue making the demi-sec and moelleux wines and let Chenin Blanc show its full range of magic.

Although some producers in the Loire have experimented with new oak, traditionally wines from Chenin Blanc are fermented in neutral vessels and aged in bottle. Huet’s wines never spend time in new oak nor do they go through malolactic fermentation. Chenin’s high acidity requires the softening touch sugar even for the dry wines. Huet secs have sugar levels of 6-7 g/l, compared to 2 g/l for most dry wines, while demi-sec typically has 20-25 g/l. The high acidity, however, makes these wines taste merely off-dry. The sweetest style is moelleux (meaning “marrow” for the unctuous texture), which has 40 to 60 g/l of sugar. Moelleux wines labeled Premiére Trie, such as this one from 2005, are wines comprised of grapes picked from an individual pass through the vineyard at harvest. What they all have in common is a bracingly high level of acidity, which enables them to improve in the bottle for decades.

The Sweet Taste of Spring

Trick your taste buds into thinking it’s warm outside with these three spring desserts and wine pairings

Forget the forecast for snow and bone-chilling temps this week, the calendar says it’s spring. So while we may be still wrapped up in wool sweaters, there is no reason not to, at least culinarily, embrace the new season while we wait for Mother Nature to catch up. (All recipes are at the end).

Moscato d’Asti with Lemon Friands

With its blend of orange blossom and peach, this bright, refreshing, medium-sweet sparkler from Oddero is like spring itself in a glass. In recent years, Moscato d’Asti has enjoyed a surge in popularity thanks to certain rap artists who took a liking to it. While celebrity-endorsed wines would normally be something I’d steer clear of, Moscato d’Asti from a good producer, served with the right food in the right setting, can be an absolute pleasure. These are crowd-pleasing, uplifting wines perfect for brunch, with appetizers, or a light dessert like these lemon friands.

As its name implies, this semi-sparkling wine hails from the Asti region in northwestern Italy, home to its more famous cousin Asti Spumante. Both are made from the Muscat Bianco grape and fermented in a stainless steel tank under pressure. But whereas spumante is made into a full sparkling wine with alcohol levels of around 7.5%, Moscato is a slightly less bubbly frizzante with a maximum alcohol level of 5.5%. Oddero is a well-known Piedmont producer of traditional, long-lived Barolos, but a small portion of their vineyard is dedicated to Moscat bianco, from which they make small batches of their Moscato d’Asti. 2012 Oddero Moscato d’Asti, (750 mL), $21.99.

Ruster Ausbruch with Frozen Orange Muscat Mousse and Mangos

Few areas in the world have the right conditions for the growth of Botrytis cinerea, the magically transformative fungus responsible for making luscious dessert wines, such as Sauternes. One of these regions is along the west coast of the Austrian lake Neusiedl near the town of Rust not far from the Hungarian border. Here the shallow waters moisten the western winds off the Pannonian plain, which almost guarantees a yearly harvest of these nobly rotten grapes. Ausbruch means to “break out” and is thought to refer to the fact that only botrytized grapes are picked (i.e. ones that have broken out from the bunch), but etymologically, it is related to the Hungarian word Azsú, which means dried, and is a term used for the Hungary’s sweet, botrytised Tokaji wines. In fact Rust used to belong to Hungary, and it is likely that Tokaji and Ausbruch wines came about around the same time, in the early 1600s.

Traditionally, these wines were made from Fermint grape, but today many of the wines are blends of Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Welschriesling and Traminer. The grapes are picked individually, which sometimes requires a half a dozen passes through the vineyard. The grapes are then gently pressed and fermented with native yeasts in either stainless steel or oak vat. This can take up to four months. The wine is then aged either in large oak vats (classic) or in small french oak barrels. With such concentrated, complex flavors and a vibrant acidity, these stand among the world’s best and most long-lived wines. You’re unlikely to find any dating from earlier than 1945, however, as the Russians occupied Rust during WWII and drank every last bottle. Feiler-Artinger is one of the region’s top producers. This Pinot Cuvée is made from Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Neuburger and Chardonnay. It was aged in small oak barriques for 18 months and tastes of apricot, honey, and orange zest with slight woody notes. At 16 years old, this wine is still in its youth and would easily keep for your great grandchildren to enjoy. But it’s drinking so well right now that I doubt it would last long in anyone’s cellar. 1998 Feiler-Artinger Ruster Ausbruch Pinot Cuvée, 375 mL, $31.99.

Sparkling Demi-Sec Rosé with Panna Cotta and Balsamic Strawberries

From the appellation of Bugey in far eastern France comes this unusual sparkling rosé from Lingot-Martin. Gamay and Poulsard grapes are used for these wines, which reflect the area’s proximity to Burgundy to the west and the Jura to the north. The Cerdon vineyard, one of only three named vineyards, consists of two south-facing slopes surrounding the village of Cerdon. A particular feature of this area’s sparkling wines is that they are made using the méthode ancestrale. This process differs slightly from the méthode traditionnelle, which is used to make Champagne, in that following primary fermentation in stainless steel tanks, a second dose of yeast and sugar is not added before bottling. Instead, fermentation is halted before all the sugars have been converted to alcohol, and the wine is then bottled with the remaining yeast. Secondary fermentation still occurs in the bottle, but the resulting sparkling wine is medium sweet. This particular wine was made for this dessert. It’s an ideal match in weight, sweetness (the wine is only just slightly sweeter), and flavors, with the acidity and bubbles providing a perfect foil for the panna cotta’s creaminess. NV Lingot-Martin Cerdon Pinot Cuvée, 750 mL, $18.99.

RECIPES

Lemon Friands

1 3/4 sticks unsalted butter

1 C + 2 TBSP confectioner’s sugar, sifted

1/3 C all-purpose flour

1 C ground almonds

5 egg whites

1 TBSP finely grated lemon or orange zest

Heat oven to 400° F. Melt butter and allow to cool. Brush muffin pan with melted butter. Sift flour and confectioner’s sugar together. Stir in ground almonds. In a separate bowl, beat egg whites gently until light and frothy. Fold them into dry ingredients. Pour in remaining butter and lemon zest and stir well. Put greased muffin pan on cookie sheet and fill 3/4 full with mixture. Put sheet and muffin pan in center of oven for 10 minutes. Remove and turn out friands onto cookie sheet. Cook for 7 to 10 minutes more. Should be golden on top and firm to the touch in the center. Remove sheet from oven and let stand for 5 minutes. Invert each one onto wire rack. When cool, dust with confectioner’s sugar. Store in airtight container.

Frozen Orange Muscat Mousse and Mangos (Adapted from the recipe: Almond Cookie Cups with Sauternes-Poached Apples and Frozen Sauternes Mousse (which is also delicious) on Epicurious)

For mousse

3/4 cup sweet dessert wine (such as Sauternes or orange Muscat)

1/2 cup sugar

4 large egg yolks

1 cup chilled whipping cream

For Almond cups

3 tablespoons all purpose flour

2 tablespoons (1/4 stick) unsalted butter, melted

2 tablespoons (packed) golden brown sugar

2 tablespoons light corn syrup

1/4 cup (about 1 ounce) finely chopped toasted almonds

Make mousse:

Whisk wine, sugar and yolks in medium-size stainless steel bowl until well blended. Set bowl over saucepan of simmering water (do not allow bottom to touch water) and whisk until thermometer registers 170°F and mixture is thick enough to fall in heavy ribbon when whisk is lifted, about 5 minutes. Remove from over water; whisk until mixture is cool, about 3 minutes. In another medium bowl, whisk cream until medium-firm peaks form. Fold cream into wine mixture in 2 additions. Cover mousse; freeze until firm, at least 4 hours. (Can be made 4 days ahead; keep frozen.)

Make almond cups:

Preheat oven to 400°F. Line baking sheet with parchment paper. Set 2 small custard cups or ramekins on work surface, bottom side up. Stir first 4 ingredients in small bowl to blend. Mix in almonds. Separately drop 2 level tablespoonfuls batter onto prepared baking sheet, spacing 6 inches apart. Using moistened fingertips, press each to 2-inch round. Bake cookies until deep golden (cookies will spread to about 5-inch diameter), about 7 minutes. Let cool on sheet until set enough to lift without tearing, about 1 minute. Using metal spatula, lift hot cookies 1 at a time and drape over cups, gently pressing to cup shape; cool. Remove from cups. Refrigerate baking sheet 2 minutes to chill quickly. Repeat with remaining batter, making 2 cookies at a time. (Cookies can be made 4 days ahead. Carefully enclose in resealable plastic bags and freeze.) Place 1 almond cookie cup on each of 6 plates. Fill each with scoop of mousse. Top with freshly cut mangos.

Panna Cotta with Balsamic Strawberries (from Ina Garten)

1/2 packet (1 teaspoon) unflavored gelatin powder

1 1/2 tablespoons cold water

1 1/2 cups heavy cream, divided

1 cup plain whole-milk yogurt

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

1/2 vanilla bean, split and seeds scraped

1/3 cup sugar, plus 1 tablespoon

2 pints (4 cups) sliced fresh strawberries

2 1/2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

1 tablespoon sugar

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Freshly grated lemon zest, for serving

In a small bowl, sprinkle the gelatin on 1 1/2 tablespoons of cold water. Stir and set aside for 10 minutes to allow the gelatin to dissolve. Meanwhile, in a medium bowl, whisk together 3/4 cup of the cream, the yogurt, vanilla extract, and vanilla bean seeds. Heat the remaining 3/4 cup of cream and the 1/3 cup of sugar in a small saucepan and bring to a simmer over medium heat. Off the heat, add the softened gelatin to the hot cream and stir to dissolve. Pour the hot cream-gelatin mixture into the cold cream-yogurt mixture and stir to combine. Pour into 4 (6 to 8-ounce) ramekins or custard cups and refrigerate uncovered until cold. When the panna cottas are thoroughly chilled, cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate overnight. Combine the strawberries, balsamic vinegar, 1 tablespoon sugar, and pepper 30 minutes to 1 hour before serving. Set aside at room temperature.

To serve, run a small knife around each dessert in the ramekin and dip the bottom of each ramekin quickly in a bowl of hot tap water. Invert each ramekin onto a dessert plate and surround the panna cotta with strawberries. Dust lightly with freshly grated lemon zest and serve.

The Magic of an Aged Auslese

Consider yourself warned. Go ahead and try those young, dry Rieslings. Delicious as they are, however, they may just turn out to be gateway wines, leading to all kinds of Riesling cravings. One particularly enticing style that is often overlooked is Auslese, which Eric Asimov calls one of “the greatest wines that nobody drinks.”

One of the reasons this style is so under appreciated is that no one is ever sure what to expect. Will it be dry or sweet? How sweet? What do you pair it with? As described in my earlier post Germany’s best wines (Prädikatswein) are categorized according to the ripeness of the grapes when picked, ranging in sugar levels from kabinett to trockenbeerenauslese. Auslese wines fall somewhere in the middle and are made from fully ripe, specially selected, sometimes lightly botrytized grapes. Regardless of sugar levels, Riesling’s searing acidity and ample fruit flavors make all of these styles age worthy, often for decades, and therein lies its magic. The wine’s fresh fruit flavors recede and integrate with the minerality, which comes to the fore along with the classic petrol notes. The sweetness softens, while the acidity keeps the wine fresh. The result is a harmonious, balanced, exquisite wine.

Those of us without the foresight (or awareness) back in the early 90s to sock away German Rieslings need to rely on those that did. Here in New York, some retailers such as Chambers Street and Crush have stocks of older vintages. I found two auslesen from 1993 that represent this style’s range of expression.

At one end of the spectrum was this auslese by Weingut Schwaab-Kiebel. Made from grapes grown and hand picked in the famed Erdener Treppchen vineyard, a steep, south-facing slope in the mid-Mosel, the wine is vinified in the traditional 1000 liter fuders. This wine was completely captivating with its notes of apple, honeysuckle, and petrol, the signature scent of an aged Riesling. More surprising was its ability to pull off seemingly contradictory feats. How could it manage to be both creamy and finely chiseled at the same time? Such is the allure of aged Rieslings.

Weingut Forstmeister Geltz-Zilliken thought to age their wines themselves and only last year released their 1993 auslese. Zilliken is based in the cool corner of the Saar River, a tributary of the Mosel, and is one of the top producers in the region. Most of their 11 ha of vineyards are in the famous, top-tiered Saarburger Rausch, where the grapes from this wine originated. It’s an area more exposed to cold easterly winds, which gives their wines a certain steeliness. What stands out for this wine is the bright lemon color, which you would not expect from a wine entering its third decade. The aromas are predominantly of ripe red apple and pear with a slight hint of petrol. It’s just off dry, with a deep concentration of fresh fruit, but is surprisingly light and delicate. After I let the wine sit open to the air for a few hours it settled into itself, with all the elements fully integrating and the petrol, mineral notes moving more to the fore.

With their bright acidity, Rieslings are one of the most complimentary wines to have with food. Too, a hint of sweetness softens the heat in many spicy Asian dishes. The Schwaab-Kiebel would be wonderful with a creamy, soft-rind cheese, but is so utterly delicious, I’d just drink it all on its own. The Zilliken, on the other hand has a silky, refined elegance that would make it a perfect accompaniment to lighter fare, such as a smoked trout salad.

Food Pairings

Cheese is a natural match for a slightly sweet wine. In the same way that quince paste and Manchego or fig jam and blue cheese work well together, sweet and salty are a natural pair. Winnimere from The Cellars at Jasper Hill in Vermont won the Best in Show at last year’s annual American Cheese Society Conference. It’s made from unpasteurized cow’s milk, wrapped in spruce bark from a Vermont farm and washed in a lambic-style beer from the nearby Hill Farmstead Brewery. The best way to eat it is by slicing the top off and scooping out the creamy, gooey cheese with a spoon. A Vacherin Mont d’Or, (when in season around the holidays) or an Époisses would also be beautiful.

Another great option is Hook’s Cheese from Mineral Point, Wisconsin made headlines in 2009 when it released a 15-year-old cheddar, which at the time was the oldest cheese sold to the public. Even at $50 a pound, it was a hit and sold out quickly. They’ve released a batch every year since, and there’s talk of releasing a 20-year-old cheddar next year. My fingers crossed. The 15-year cheddar is pretty spectacular. It’s so crumbly that slicing is futile. You end up eating little boulders that fall off the block, and they just melt in your mouth. The texture is surprisingly creamy and smooth with little bits of crunchy calcium lactate crystals. It’s only slightly younger than the wine but packed with so much flavor the wine only barely stands up to it.

I ♥ German Riesling

Or What We Talk About When We Talk About Residual Sugar

Ask any sommelier what his or her favorite grape variety is and chances are German Riesling will be at the top of the list. Ask again what the toughest wine to sell is and you’ll likely get the same answer: Riesling. Why such a huge disconnect? In a word, sugar. Among the general wine-drinking public the perception persists that all German wine is sweet (in fact much of German wine is dry), but more erroneously that sweet equals bad.

I recently pulled out a bottle from the Mosel for a friend, who cast a wary eye at me when she saw the distinctive long, slender bottle. She took a sip, then another, and was genuinely surprised: “Oh, this is good. It isn’t sweet at all.” While some sweet wines are indeed bad, they are bad not because they are sweet but usually because they are unbalanced and simple. This wine was good not because it was dry, but because it had a beautiful concentration of fresh fruit, and the residual sugar present in the wine (yes, there was some) was balanced by a firm streak of acidity.

Acidity is the key when it comes to any wine with residual sugar. It turns out, however, that with German rieslings, I’ve been thinking about this backwards. I’ve always thought of it as sugar needing acid, but in the northern climates of Germany’s wine-growing regions where grapes often struggle to ripen, it’s just the opposite. Riesling is a grape with naturally high acidity, and here, even in summer, the nights can be cool, which means that a lot of that acid sticks around late into the harvest season. It’s this acidity that needs a bit of sugar to soften what otherwise might be some razor sharp edges.

Vineyard site, then, becomes very important. There are excellent Rieslings made in the Rheingau, Pfalz and Nahe, but where Riesling reaches its height in finesse and delicacy is on the steep, south-facing slopes along the snake-like Mosel River. The best vineyards are planted with a southerly aspect, which allows the grapes to capture as much sun as possible, giving them time to develop sugars and concentrated flavors well into November. This confluence of climate and terroir is what makes Rieslings from the top vineyards and top producers in the Mosel so radiant. Whether it’s dry, off dry or sweet, what you get is a harmonious trifecta of fruit, acid and sugar. When made well, they are structured, well-balanced, glorious wines that are incredibly versatile with food. It’s what makes them so revered by sommeliers.

“A German wine label is one of the things life is too short for . . .” Kingsley Amis

With all those umlauts and syllables strung together in long breathless stretches, a German wine label can seem as impenetrable as German existentialist philosophy. They do, however, contain a surprising amount of information. First and foremost, to gauge the sweetness of a wine look for the word trocken for dry, halbtrocken for half-dry, or feinherb for slightly sweeter (although this term has no legal definition, it is often found on labels). Lieblich and Süss are for sweeter wines, but they are rarely used. If none of these terms are on the label, then look for the alcohol level. If the abv is 11 or 12%, the wine is likely to taste dry; if it is lower, expect some sweetness.

Just to make things more complicated, in 2012, the VDP—a group of around 200 top producers who have taken quality assurances into their own hands—gave us a few more terms to decipher. One of their goals is to emphasize and recognize wines by the quality of the vineyard sites (as is done in Burgundy). On newer wine bottles you will see Grosses Gewächs, which means a wine from one of the very best sites, a Grosse Lage. In essence, grand cru wines, and they are always dry. Erste Gewachs wines are the equivalent of premier cru, Ortswein are village wines, while Gutswein are regional. VDP member wines are identified by a band around the bottleneck with the symbol of an eagle clutching a cluster of grapes.

Traditionally, quality wines have been classified by their must weights when they are picked, and these terms are still used. The longer the grapes stay on the vine the heavier the must weights, the greater amount of sugar, and the deeper and richer the flavors. Kabinett grapes are harvested first (these are not allowed for Grosses Gewächs), followed by spätlese (late harvest), and then auslese (selected harvest). Beerenauslese and trockenbeerenauslese are made from grapes left to dry on the vine and are often affected by botrytis (noble rot). These last two are lusciously sweet dessert wines that can age for decades, while the first three can be made in a range of styles, from dry to sweet.

Although the dry Rieslings can be delicious, it’s the sweet versions of spätlese and auslese, which are made nowhere else in the world that make German wines unlike any other. These wines are often not fermented to dryness and therefore will have some residual sugar (even trocken wines can have up to 9g/L of sugar). Traditionally, however, they weren’t meant to be consumed until they had been aged. Spätlese wines will initially be very fruity and fresh, then shut down and enter an awkward phase. They need at least 10 years to really shine but will be delicious for another 20. Auslesen need a couple of decades, but will last for at least half a century. Over time, the intensity of the ripe fruit fades, allowing the minerality to come through. The acidity and sugar amounts technically remain the same but their edges soften and they become more integrated. What remains is a leaner, more complex, spectacular wine. They pair well with roasted game, such as duck, ham, smoked trout and cheese.

As with any other wine region the key to finding good wine is knowing who the good producers are. Recently, a group of top winemakers were in New York for Rieslingfeier, an annual event to promote top quality German Rieslings. I attended a seminar hosted by Stuart Spigott, a wine writer based in Berlin whose book The Best White Wine on Earth –The Riesling Story is coming out this summer. Four notable producers from the Mosel and Rheingau poured their wines, and although most were dry (and fantastic), their other wines are worth seeking out. Whether dry or sweet, these are producers worth knowing about.

Karthäuserhof is one of the most highly regarded estates in Germany and, unusually, is a single vineyard. Located along the Ruwer River, a tributary off the southern part of the Mosel, the vineyard comprises 19 ha of blue Devonian slate. The estate is known for its finely made Rieslings, though it also makes a small amount of Pinot Blanc and sparking wines. Evidence of winemaking in the area can be traced back to the Romans, but it was the Carthusian monks in the 1300s who brought acclaim to these wines. Today’s winemaker Christian Vogt brought two trocken wines from 2012. While both had 8 g/L of sugar these wines tasted bone dry and had a quite pronounced minerality to them.

Weingut Peter Lauer has at its helm, Florian Lauer, a fifth-generation winemaker, who is one of the rising stars in the Mosel. Lauer has 8 ha of Riesling along the Saar River, off the southern part of the Mosel. It is slightly cooler and the wines in general have a steelier, chiseled edge to them. One of the most famous of Lauer’s vineyards is Ayler Kupp. It is also quite sizeable, and different parts have different soil, microclimates and sun exposure. Lauer believes in letting the grapes express the terroir so he harvests, vinifies and bottles these parcels separately. He also eschews the pradikat classification (kabinett, spätlese, auslese), Instead you will see Fass numbers, indicating wine from a specific parcel. He also likes to indicate the exact location so you’ll fine “Unterstenbersch” (the bottom), Stirn (the top) and Kern (mid slope) appended to the vineyard name. He uses native yeasts and will let the wine rest on its lees for six months. The wines we tasted were also from 2012. The Ayler Kupp “Unterstenberg” has 12 g/L of RS, and was richer and creamier than the Karthauserhofs, it still tasted dry. The Ayler Kupp “Stirn” had 30 g/L of RS and was merely off dry. Absolutely delicious.

Clemens Busch, the eponymous owner of Weingut Clemens Busch, is a bit of a rock star in the Mosel. Jerry Garcia perhaps, in that he farms his 25 ha in the mid-mosel biodynamically, and he has a devoted following. In the cool folds of the Mosel this means he must climb the steep slopes every ten days to apply an herbal tea to fight fungal disease. He too believes in the expression of individual terroir and picks, ferments and bottles each of his parcels separately. Bottles are labeled with their respective parcels: Fahrlay, Falkenlay, Raffes, Rothenpfad and Marienburg. The wines are generally richer, fuller bodied with a striking minerality.

Weingut Leitz is one of the top producers in the Rheingau, where winemaker Johannes Leitz has been making wine since he was 21. The vineyards were his playground while growing up, but once he was old enough, he took over from his mother who’d been at the helm since his father died in 1965. Leitz manages nearly 40 ha of vineyards in the western part of the Rheingau where the soil consists of slate and quartzite. Leitz often picks his grapes late and lets them macerate on the skins for 36 hours. He will then often ferment them dry. We tasted the 2006 Rudesheimer Berg Rottland Alte Reben, which was a big, bold, full-bodied wine with racy acidity and tasted of ripe tropical fruits (pineapple) and lemon. The 2009 Rudesheimer Berg Kaisersteinfels was crisp and dry, very precise with mineral and petrol notes.

A New Wave of Pineau Interest?

The last time Pineau des Charentes was fashionable François Truffaut was making a little movie called Jules et Jim. Not since the 1960s has it been cool to order a pineau in Paris. Even today requesting this sweet aperitif made from Cognac and grape must you risk a waiter’s derisive snicker (this is probably true for any American trying to order in a Parisian restaurant). Although this vin de liqueur from the Cognac-producing region of western France has been around since 1589, for most of its 500-year existence it has mostly remained a regional specialty consumed by locals. Up until recently, as much as 90% of production remained in the region with Belgium drinking the rest. In the last few years, however, bottles from some top producers have been reaching foreign markets, including the U.S., where they are popping up on some highly regarded New York wine lists: Per Se, Rouge Tomate, Le Bernardin and The Musket Room.

Pineau’s origin is that of a happy accident when a Cognac producer mistakenly dumped a load of grape must in a vat that still held a bit of Cognac. A year later he realized what had happened but decided that the concoction was delicious. Today it’s essentially made the same way by adding the previous year’s eau de vie (to be called Cognac it must be aged a minimum of 2 years) to freshly pressed, unfermented grape must in a ratio of 1:3, which is technically what makes it a vin de liqueur. With fortified wines, such as port or vin doux natural, fermentation is allowed to begin but is then halted before all the sugar ferments to alcohol. This seemingly slight difference in technique has a noticeable effect on taste since the process of fermentation produces specific flavor compounds. A vin de liqueur will retain the fresh fruit flavors of the grapes. Those used in white pineau are the same as those for Cognac: Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche and Colombard, with occasional Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Montils. These are all high-acid grapes, which help prevent spoilage when making Cognac. The use of sulfur is forbidden as its flavors become concentrated through distillation. The acidity is also critical to balance out the sweetness in the final wine (a common theme with sweet wines). For the red and rosé pineaus, the same grapes as those grown in Bordeaux are used: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc. Alcohol levels range from 16 to 20%.

Much of the complexity is derived from the aging process. The wines must be aged a minimum of 18 months, with at least 12 months spent in oak barrels, which infuses the wine with hints of vanilla and oak. Wines labeled “Vieux” have spent 5 years in oak, while those labeled “Tres Vieux” have been aged 10 years or more in barrel. Jacky Navarre and Marie-Paul & Fils age some of their pineaus for 25 and 30 years and are extraordinary wines. The French traditionally drink pineau ice cold as an aperitif, but it also makes for an exceptional after-dinner drink, especially those that have been long aged.

Here are some to try:

Bernard Boutinet Pineau des Charentes, NV, 375 ml half bottle, $15. The Boutinet family has been growing grapes and making Cognac for more than 150 years. Ugni blanc and colombard grapes are the main grapes in their Cognac, which is then blended with must from Colombard grapes to create their white Pineau des Charentes. They also produce a rosé pineau using merlot and cabernet sauvignon.

Pierre Ferrand Pineau des Charentes, NV, 750 ml, $25; 17% abv. This wine was aged the minimum 18 months, 12 of those in oak cask. It is silky smooth and mildly sweet with notes of fresh grapes, peach jam, honey, orange marmalade, prunes, vanilla and oak. All those high-acid grapes keep this delightfully refreshing.

Jean-Luc Pasquet Pineau des Charentes, NV, 750ml $30. Jean-Luc began farming organically in 1995. He uses wild yeasts and does not add sulfites. His pineau is made from ugni blanc and montils and is aged at least 18 month in oak barrels.

Navarre Pineau des Charentes Rosé, Vieux, 750 ml, $69. Jacky Navarre is a fourth-generation Cognac producer who hand harvests his grapes. One hectare out of his 11 is used for pineau production from which he makes a variety of styles. For his rosés Navarre uses cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc grapes. The must is fortified with six-year-old Cognac (not the usual year-old eau de vie), and spends five years in barrel.

Navarre Pineau des Charentes Tres Vieux (30 years old), 750 ml $70. An extremely rare and unusual pineau. Back in 1982 Navarre mixed his newly crushed grape must with six-year old Cognac then sent the wine into barrels where they spent the next 30 years before being bottled in 2012. The result is a lusciously full-bodied, complex wine that tastes of toffee, cinnamon, baked apples, dried figs and walnuts. This is an excellent wine for dessert rather than as an aperitif.

Paul-Marie & Fils Pineau des Charentes Tres Vieux White NV, 750 ml, $75. This is the label of Nicolas Palazzi, an importer and negociant who buys Cognac and pineau and ages them, some for decades. These pineaus are remarkably complex and refined, not to mention delicious.

Paul-Marie & Fils Pineau des Charentes Hors d’Age 25 years #6, Red, 750 ml, $75. Extremely elegant wine with a lighter bodied than the Navarre 30-year-old pineau, with a more snappy acidity. The Cognac flavors are very much evident along with caramel and raisins.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next →